The Saga of the Leonard Family Ironworkers Memorial (That Never Was)

By Eric B. Schultz

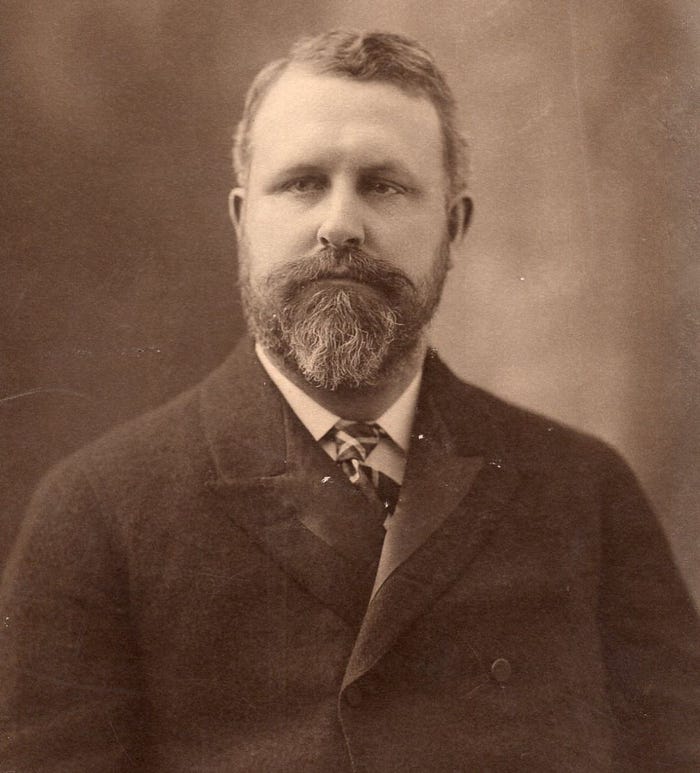

At a July 1899 meeting of Taunton’s Common Council, Mayor Nathaniel J.W. Fish¹ announced that he had received a letter from Lewis A. Leonard, a New York newspaperman, local history author, and President of the Leonard Family Association.² Lewis asked if the city would partner with the family to erect a monument dedicated to the history of the iron industry, featuring the Leonard family’s contributions.

While Fish lacked details about the project, he must have known that few families were more closely associated with Taunton and its rich industrial history than James Leonard (1621–1691) and his descendants.

The Leonard Family: An American Success Story

More than 250 years earlier, Taunton had invited Ralph Russell and brothers James and Henry Leonard to erect a bloomery (to manufacture cast and wrought iron) on the Two Mile (today’s Forge) River. Immigrants from Wales, the Leonards were experienced ironworkers employed at Hammersmith Ironworks on the Saugus River.³ While Henry would stay briefly in Taunton and then move on to organize ironworking ventures elsewhere in Massachusetts, New Haven and New Jersey, James made Taunton his home.

The Raynham forge was capitalized in 1652 by James and 45 other shareholders, including 20 of Taunton’s first families. The town provided bog ore and timber from common land and allowed the Two Mile River to be dammed for power. By 1656, this modest but well-run bloomery produced 20 to 30 tons of iron annually. Investors would receive 12%-15% returns each year for nearly a century. Most importantly, the Old Colony had established a dependable local source of iron for agricultural tools and shipbuilding.⁴

James Leonard became a “principal workman” at the Raynham Forge. By 1683, his son, Thomas, managed the ironworks.⁵ Already known as the Ancient Iron Works by the end of the 18th century (and “Anchor Forge” under 19th-century ownership), this long-lived factory produced iron until 1876, becoming the mother of new ironmaking ventures throughout the Old Colony.⁶

For example, James founded a second bloomery in the 1660s, Whittenton Forge on the Mill River, an ironworks operated by the Leonard family until 1807 (and the site of today’s Whittenton Mills Complex). Thomas took his experience at Raynham Forge and, with brother James, erected the Chartley Forge sometime after 1695 in present-day Norton (at today’s Chartley Village), an ironworks that would operate until nearly 1800.

In 1720, grandson James Leonard built a forge in present-day Easton called Brummagem, managed by his son, Eliphalet. These early efforts in developing water power in Easton paved the way for another remarkable Old Colony industrialist, Oliver Ames, to launch his shovel-making business.⁷ Thomas’s son, Elkanah Leonard, helped to fund King’s Furnace in East Taunton (on land now part of Massasoit State Park) in 1724.⁸ Fifteen years later, Zephaniah, a great-grandson of the first James Leonard, founded a new bloomery on Mill River.⁹ In 1788, two Leonard ironworkers in James’s sixth generation were granted a monopoly and tariff from the Massachusetts General Court to protect their invention of a new way of blistering steel.¹⁰

James and his wife, Mary Jane Martin, had nine children, including six sons, five of whom became ironworkers. By 1690, James and Mary (who died in 1663) had 68 grandchildren.¹¹ For seven generations after James and Henry arrived in New England — from a generation after the Mayflower until nearly 1800 — people knew, “Where you find ironworks, there you will find a Leonard.”¹²

Historian Stephen Innes writes, “The constancy with which the Leonards stuck to ironworking over successive generations was extraordinary.”¹³ The historian of the Saugus Ironworks, Edward Neal “E.N.” Hartley, refers to the Leonards’ role in helping establish British North America’s cast and wrought-iron industry as “the very epitome of the American success story.”¹⁴

The Leonard family spread nationally to include beauty and political fame. The clan counted among its numbers Helen Louise Leonard, known as the beautiful and stylish Lillian Russell. A second Helen Leonard, born in Assonet and descended through James’s son, Thomas, was the mother of John Hay, private assistant to Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State under Presidents McKinley and Roosevelt.

Opening Complications: Land and Scale

Given this celebrated history, Fish supported the idea of a national monument dedicated to the Leonards and ironmaking, which might turn Taunton into a tourist destination. “The feeling is that the City of Taunton should select and donate the land,” Fish told the Council, “the Leonard family build the base, and the iron industry erect the monument.” Fish authorized the Joint Special Committee on a Memorial to Robert Treat Paine to investigate the possibility of erecting such a memorial.¹⁵

The mayor might have anticipated that land would be a complication. The statue honoring Robert Treat Paine, slated to cost $15,000, seemed destined for a prime location at City Hall Square.¹⁶ Meanwhile, “a generously disposed citizen,” Cyrus Lothrop, planned to donate a soldiers and sailors monument to the city. “It is understood,” the paper reported, that Lothrop had received “a partial promise that it shall be placed upon the Green.”¹⁷ Lothrop was a wealthy iron manufacturer whose brother-in-law, Oliver Ames, was the former Governor of Massachusetts.

To complicate matters further, if the Leonards wanted their memorial in the center of Taunton Green, it would have to replace the existing Marvel Fountain given to the city in 1882 by William D. Marvel. Marvel’s gift was conditioned on the promise that it be placed near the center of the Green and kept in running order. Since Marvel also made his fortune in iron, there was speculation that he might agree to move his fountain for such an iconic memorial as the Leonards had proposed.¹⁸

Fish soon learned that land was only one of several complications. The Leonards would propose a memorial that might rise 90 feet, have a diameter of 60 feet, and cost as much as $200,000. By comparison, the Robert Treat Paine memorial would rise 21 feet and cost $15,000.¹⁹

A Small Army on the March

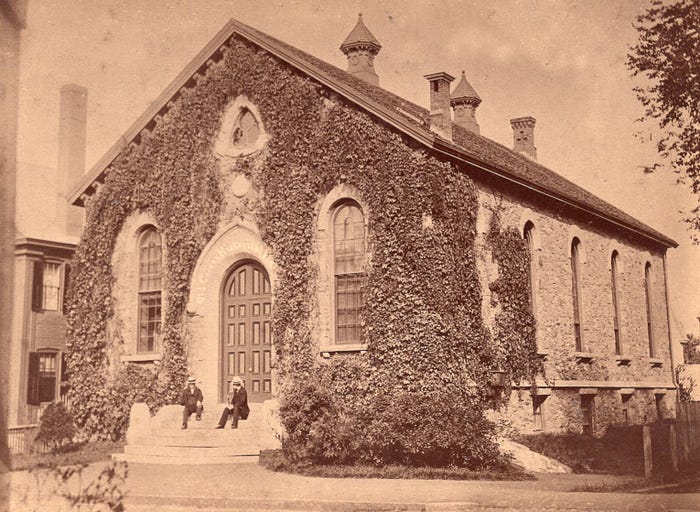

What seemed a good if complex idea to Taunton’s mayor in 1899 gained momentum in 1901 when some 400 members of the Leonard family from 29 states assembled in Taunton for a family reunion. Meetings were held at the Old Colony Historical Society’s former headquarters at the Union Mission Chapel on Cedar Street. The Old Colony’s Secretary and Archivist, James Seaver, would become instrumental in efforts to establish what was now being called “the Ironworkers Monument.”

The Leonard family organized itself like a small army on the march. The family named 11 Vice Presidents, from William H. Fox, a former mayor of Taunton and future presiding judge of the First Bristol Court, to the Right Rev. Abiel Leonard of Montana, soon to be elected Bishop and appointed head of the Episcopal Church in Utah and Nevada.

The summer 1901 meetings also included the formation of an executive committee and an impressive memorial committee responsible for memorial design and fundraising. This active, “boots on the ground” team included Franklin Leonard Jr. of New York, Henry M. Lovering of Taunton, F.C. Leonard of London, Canada, Job M. Leonard of Fall River, and President Lewis A. Leonard.²⁰

Henry Morton Lovering (1840–1918) was the grandson of Marcus Morton, a Taunton native and two-term state governor. Lovering served as Treasurer of his family’s enormous and successful cotton factory, Whittenton Mills. He had been a classmate of John Hay at Brown University. Lovering served as president of the Taunton National Bank, president of the Old Colony Historical Society, and on the Taunton Common Council and as an Alderman. He was also the city’s water commissioner for 45 years.²¹

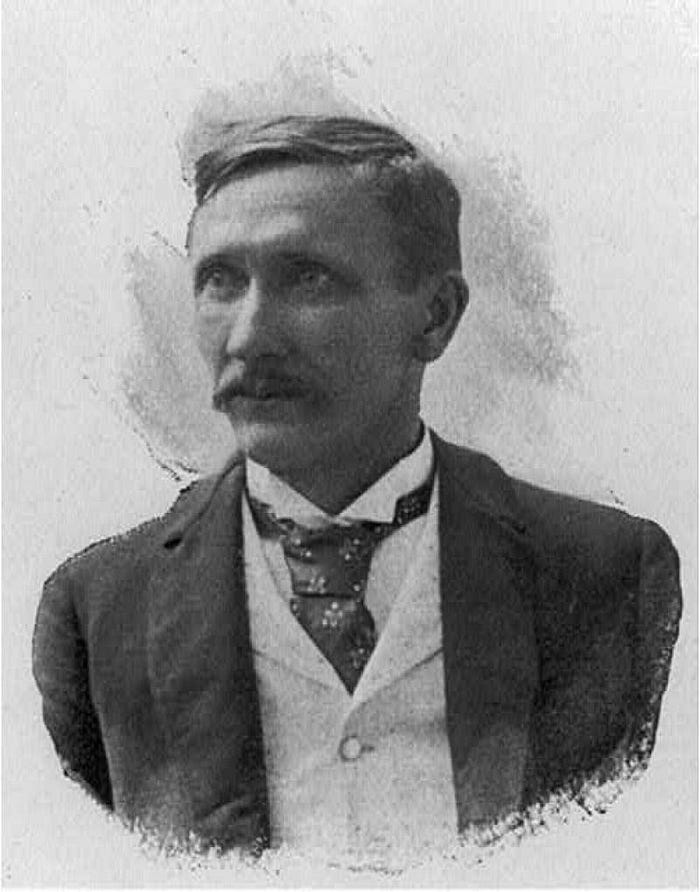

If Lovering’s role was to encourage the city council to find land for the project, it was Job Mason Leonard of Fall River whom the family association would look to as perhaps the key mover and local funder of their grand design. Job was the only Leonard appointed to both the Executive and Memorial Committees.

Born in Raynham in 1824, one of 21 children of Job and Polly (Lincoln) Leonard, Job had fled the family farm in 1850 to found the East Bridgewater Iron Company. Five years later, he organized the hugely successful Mount Hope Iron Works in Somerset, employing (at its peak) 500 workers to manufacture nails and plate iron. Job’s only son, Henry, was the company’s agent and general manager.²²

Not only was Job wealthy and the model of a successful Leonard ironworker, but he also demonstrated an interest in the art and power of sculpture. In April 1899, he had placed a granite statue of “Hope” in front of his Leonard family lot not far from the entrance of Mayflower Hill Cemetery. It was a “large size and a notable ornament,” the paper reported, in a cemetery that was “yearly putting on more beauty.”²³

It’s risky to read too much into Job’s Mayflower Hill monument. His grandson, Ralph, had died tragically of typhoid on a school trip in Paris in August 1894. Ralph’s mother and Job’s daughter-in-law, Annie (Hood) Leonard, died in 1898. Job’s wife, Caroline (Field) Leonard, would die in October 1900. Perhaps the statue of Hope was placed in honor of Ralph and Annie or anticipating his wife’s loss — and even, at age 77 with chronic health problems, his eventual death.

An Embarrassment of Riches

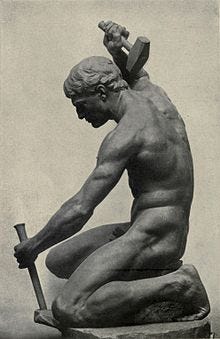

Shortly after the Leonard family’s July 1901 organizational meeting, acclaimed American sculptor Charles Henry Niehaus was contracted by the Leonard family to design the memorial. Niehaus visited Taunton and examined locations for the proposed Leonard monument with the city engineer. Not surprisingly, Niehaus dismissed the idea of building a new park at the location of the Ancient Ironworks in Raynham and concluded that a work of this stature must sit in the center of Taunton Green.²⁴

Niehaus (1855–1935) was known for his neoclassical style and his numerous public monuments, including a statue of President James A. Garfield (1887) and several figures at the National Statuary Hall in the Capitol. His plans for the Leonard monument were compared to “the great Lincoln monument at Chicago”²⁵ designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, dedicated in 1889, and considered one of the finest pieces of public art in the 19th century.²⁶

However, the sculpture that most intrigued the Memorial Committee of the Leonard Family was Niehaus’s 1901 memorial in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in honor of Edwin Drake, the first American to drill for oil successfully.²⁷

Despite Niehaus’s fame and talent, and the Leonards’ close ties to city officials, approval to place a colossal neoclassical monument in the center of Taunton Green was no foregone conclusion. An article in The Taunton Herald-News on Saturday, January 4, 1902, said, “Taunton is soon to suffer from an embarrassment of riches, in the shape of monuments, and the question what will be done with them? Is already agitating the minds of a few.”²⁸

The First Miscalculation

An optimistic letter from Lewis Leonard to Henry M. Lovering suggested that the family might lay the monument’s cornerstone in the summer of 1902. Leonard wrote that Neihaus expected to have two models by spring 1902, available to exhibit and compare at the next Leonard family summer gathering. “We felt our way carefully,” Lewis explained, “and confidently believe that the funds to complete the monument will be forthcoming as fast as needed in the progress of the work.”²⁹

If Job Leonard was expected to be the most significant local donor, the family had even loftier national hopes. “It is expected that Andrew Carnegie will be a contributor,” the Fall River Daily Herald learned, “because he has always expressed great interest in the city where the first crude works were engaged in the business that subsequently made him many millions.”³⁰

That expectation was the first miscalculation in the family’s deliberate plans. In March 1901, Andrew Carnegie became the world’s richest man when his Carnegie Steel Company merged with two other firms to form U.S. Steel. Already one of the world’s great philanthropists, Carnegie’s retirement would bring an explosion of funding to create 2,500 public libraries worldwide. When the Leonards approached the Common Council, plans were likely in motion for Taunton to pitch Carnegie for funds. Hewing to the “Carnegie formula” required that the city provide a site and enough public monies to provide ten percent of the cost of the library’s construction to support its operations.³¹

Taunton pitched. Carnegie delivered, bestowing a $70,000 gift. The Taunton Public Library was built in 1903 — just as the Leonards may have hoped Carnegie’s munificence was funding their memorial.

An Abundant Fall of Water Which May Gush From Grottoes

Two models of the proposed Ironworkers monument arrived in Taunton in September 1902, later than desired. Niehaus had been diverted by other work, Lewis Leonard told Seaver, and a shelf in Niehaus’s studio had fallen and wholly demolished his first Leonard memorial models.³²

Old Colony has in its archives pictures of both models, but mere images hardly rise to the descriptions of early 20th-century reporters:

He [Niehaus] had made two designs consisting of groups of figures about a base, which represents a circular basin of water, and of a shaft rising from the base.

In the one the shaft rises about ninety feet in the form of an obelisk . . .the plinth has low reliefs, with figures showing man and woman plighting troth, vestal virgins caring for the fire on an altar and other groups . . . which refer to family life. The groups below are designed for bronze and show the prospector discovering iron ore, the iron master extracting metal, the smith and the artificer in iron. In this design provision is made for an abundant fall of water which may gush from grottoes on two sides of the island.

The second design is not so tall. Here the groups are more concentrated . . . On the cap of the pedestal stands a great draped female Genius holding a torch on high and in her other hand a Mercury’s helmet, with wings. The figures of the lower groups in each design are calculated for a height of eight feet. The monument will cost from $150,000 to $200,000.³³

When Niehaus’s models reached Taunton, they were widely praised. “A French artist who examined” the new models “the other day, and who spent a year in this country,” Lewis wrote in one of his optimistic letters, “insists that it will be the most attractive work of this kind on the continent.”³⁴

Nobody was sure which design was better. However, the fountain feature made clear that Niehaus intended to replace the Marvel monument in the center of Taunton Green, even if such assurance by the city had not yet been given.³⁵

I Think He Will Do Quite the Liberal Thing By Us

With Carnegie’s funding for Taunton diverted to a public library, Job Leonard’s generosity and support became essential.

By December 1902, however, Job was ill and hospitalized. Lewis Leonard wrote anxiously to Seaver, saying Job had not responded to his request for a meeting.³⁶ On January 23, 1903, the Memorial and Executive Committees gathered at Old Colony, accepting one of the Niehaus models (though it’s unclear which one) and authorizing payment for its construction “from funds contributed for such purpose.”³⁷

Despite this apparent forward motion, the Leonard family dragged its feet. Job Leonard was missing. A location for the monument had not been approved. Niehaus wrote in March 1903, saying he was anxious to begin “the work that counts.”³⁸ We do not know if he ever began.

By spring 1903, Job Leonard had recovered from surgery. Ever the cheerleader, Lewis believed “his condition certainly promises a permanent recovery and a long life.”³⁹

Job committed $1,000 to start, hoping it would encourage another dozen local Leonards to give $1,000 each and perhaps 20 to give $500. While the family had in hand “some pretty good promises in New York from the iron people,” they wanted to have the locals make a “first definite showing.” Seaver added, “I could not draw from him a promise as to what he would give in the end, but I think he will do quite the liberal thing by us.” Lewis also offered a $1,000 contribution and asked Seaver to generate a list of locals to call on.⁴⁰

The Crushing Blow

By 1904, the upbeat, promising flow of letters from Leonard to Seaver in the Old Colony archives ends. Besides the loss of Carnegie funding, we are left to speculate what might have happened.

The crushing blow to the family’s memorial project probably came in February 1904 when Job Leonard’s son, Henry, died suddenly of heart failure. Only 54, Henry was general manager and vital to the success of the Mount Hope Iron Works. Job had placed his hopes for the future in his grandson, Ralph, and son, Henry — now both gone. Henry’s death probably also marked the death of the memorial.

A year later, on May 7, 1905, 82-year-old Job Leonard died. His obituary reported that “little had been done with the business” since the death of his son in February 1904. Job’s cause of death was chronic cystitis, a painful urinary condition and probably the reason he had been hospitalized in 1902. (We don’t know what awful surgery he may have endured.) Such discomfort would have made it difficult for anyone, much less an elderly, heartbroken man, to concentrate on his business affairs. The pressure to underwrite and lead a fundraising effort may have been asking too much.

With no family member able to assume business leadership after seven generations, Job decided that the end had come. “If a Leonard cannot run these iron works,” he declared, “no one else shall.” In despair, he abruptly shuttered his Mount Hope plant, surprising his workers, Somerset, and the industry.⁴¹

In a series of rash business decisions, Job destroyed much of his creation. Instead of selling an ongoing business, he dismantled his factories, junked good machinery, and laid off hundreds of employees. He turned down a $75,000 offer — enough to fund most of the Leonard memorial — because the buyer’s plan was to continue using the purpose-built facilities for ironworking.

Perhaps more than a broken heart, Job’s sudden actions signaled a fractured company. His factory specialized in iron nails, but the world had moved to steel nails. In 1886, 10% of the nails made in America were steel; by 1892, more than 50%; and in 1913, 90% of all nails produced were steel.⁴² The competition had left Mount Hope Iron Works behind, and the cost to compete was too great, not just for a Leonard but for anyone. This rapid technological shift may suggest that Job was not nearly as wealthy as Lewis Leonard and the family association had hoped.

While Job’s actions left the village of Somerset temporarily “an industrial tomb,” the Fall River paper wrote, “the old man died triumphant as ‘The Last of the Iron Leonards.’”⁴³

Postscript

Today, the Leonard Ironworkers memorial survives only in correspondence, newspaper articles, and pictures of the elaborate Niehaus models. As memorials go, however, it’s difficult to miss the legacy of the Leonard family all over Taunton and the Old Colony.

In 1950, a marker was erected in Raynham, along South Main Street, a tenth of a mile north of King Philip Street, showing the location of James Leonard’s Ancient Ironworks.⁴⁴ James Leonard’s original home, used as a garrison in King Philip’s War, was destroyed long ago. However, the James Leonard House at 3 Warren Street in Taunton was built around 1752 by Elkanah Leonard, the great-grandson of the first James. This home still stands and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Mount Hope Ironworks was demolished in 1913, though a building associated with the business survives in historic Somerset Village, where the Historical Society gives occasional walking tours.⁴⁵ Job Leonard’s 1860 Greek Revival home at 134 South Street in Somerset comes up for sale from time to time.⁴⁶ His “Hope” statue and the Leonard enclosure at Mayflower Hill Cemetery on Broadway in Taunton still stand, with Job, Henry, Ralph, Russell, Annie, and other family members interred there.

Not far away in Plain Cemetery lies Zephaniah Leonard, the founder of Hopewell Forge. His striking raised memorial was pictured in Old Colony’s post, “In Praise of Genealogists: A Story of Early Taunton on Medium. A short walk from Zephaniah lies James Leonard Hodges, former postmaster of Taunton who served in Congress for a decade. His grandmother was Jerusha Leonard, a third great-granddaughter of the original James.

On display at Old Colony History Museum is the footstone of James’s son, James’ wife Lydia (Gulliver) Leonard, rescued from Taunton’s oldest cemetery, Neck O’ land. Lydia and her husband’s headstones, along with those of other Leonard family members, can still be viewed in this ancient burying ground on Summer Street. The bullet-ridden shutter of Daniel Leonard’s home is exhibited in the Old Colony History Museum’s new military room. A fourth great-grandson of James, Daniel was a devoted Loyalist and key figure in Taunton’s Liberty and Union story, told at “Liberty & Union: ‘They Have a Fine Flag Now.’”

When Job Leonard died in 1905, he left just one of his 20 siblings still alive. Brother Josiah R. Leonard lived another three years, passing away in May 1908 at age 96, one of Taunton’s oldest citizens. “In his early days Mr. Leonard kept a variety store on old Knotty Walk in Taunton,” his obituary read.⁴⁷

However, Josiah’s store was hardly the most famous Leonard retail establishment in Taunton. Many readers will recall Leonard’s, a landmark ice cream and confectionary shop located at 35 Main Street in Taunton, opened in 1887 by Philo F. Leonard, a 5th great-grandson of James. Unfortunately (for all of us), Leonard’s closed in 1959.

Notably, Leonard’s was not located on the Leonard Block, constructed in 1870 by George Jr. and Joseph Leonard, replacing the original Leonard family home. This prominent four-story commercial building was located at 107 Main Street, adjacent to Taunton City Hall. It housed various businesses over the years, including clothing stores like Goldstein & Antine and B.F. Stanton, as well as the J.M. Wells furniture distributor.

The building’s second and third floors were home to the Star Theatre, which opened in 1911 and operated until 1929 when the film industry transitioned to sound films. In December 2014, the historic Leonard Block was demolished to address safety issues and facilitate the adjacent Taunton City Hall renovation.

In 1888, the Leonard School was constructed on West Britannia Street in Taunton, named in honor of the ironworking family. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984 but closed in 2009.

Finally, back at Mayflower Hill, not far from Job Leonard’s Hope statue, is the Cemetery’s most famous monument. A child-sized marble rocking chair memorializes Pearl E. French, a three-year-old who died in 1882 of spinal meningitis. Visitors come from all over to leave small toys and other gifts in “her vacant chair,” sometimes said to glow or rock on its own. Visitors who wander to the back of Pearl’s family stone, however, will see the name “Leonard” carved in granite; Pearl’s mother was Emma Jane Leonard, her grandfather Horatio Harding Leonard, and Pearl’s 8th great-grandfather was the original James, whose legacy endures — monument of not — in hundreds of ways around the Old Colony.

In May 1918, a small account was opened in the name of the Old Colony Historical Society, the Leonard Memorial Fund trustee, by George A. King, Treasurer. In November 1978, the account totaled $1,096.51 — an unexplained vestige of a grand memorial that never was.⁴⁸

Footnotes:

¹ Fish was one of Taunton’s most colorful mayors, elected 1897–1899 and 1912–1915. For more, see William Hanna’s A History of Taunton, Massachusetts (Taunton: Old Colony History Museum, 2007), 237–238.

² Lewis Alexander Leonard (July 10,1845–1926), a pioneer newspaper editor and author, was born on Poplar Island in Chesapeake Bay, opposite Baltimore, Maryland; he died in Cincinnati, Ohio. His father, Nathaniel Leonard, was a ship builder. After receiving a university education, Leonard practiced law in East Maryland for a time and in Lafayette, Indiana, and then moved to Cincinnati, Ohio. Leonard was a reporter for the Enquirer before becoming editor of the old Cincinnati Star. When the Star consolidated with the Times, in June 1880, Leonard continued as editor of the Times-Star until 1882 when he was made manager. He left the Times-Star in 1884 and became editor of newspapers in Detroit and Albany, New York (Albany Time-Union). He was regarded an authority on the evaluation of newspaper plants and was employed to appraise important newspapers in Chicago and New York, including the World. Leonard was personally acquainted with several Presidents; in addition he was prominent in National Democratic conventions for a number of years, handling publicity matters. Leonard authored the Life of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, New York: Moffat, Yard & Company, 1918 and the Life of Alphonso Taft, New York: Hawke Publishing Company, Inc., 1920. Source: “Lewis Alexander Leonard Papers,” Emory University, Web, December 22, 2024, Collection: Lewis Alexander Leonard papers | ArchivesSpace Public Interface.

³ Hammersmith is preserved today as the Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service). It was the first successful, integrated iron works in the New World, producing wrought iron and cast-iron products from 1646 to approximately 1670.

⁴ Stephen Innes, Creating the Commonwealth: The Economic Culture of Puritan New England (New York: W.W. Norton), 1995, 264–265. Financial results from Hartley, Ironworks of Saugus, 273, 275–276.

⁵ E.N. Hartley, Ironworks on the Saugus (University of Oklahoma Press, 1957) rpt: 2015, Eastern National, 273–274.

⁶ Hartley, Ironworks, 274–275.

⁷ Hartley, Ironworks, 275. See also Easton Historical Society, 1993, Web, December 19, 2024, https://www.eastonmahistoricalsociety.org/uploads/1/3/2/9/132901775/10-north_easton_1993.pdf.

⁸ Lydia Cobb Quequechan Chapter of the Massachusetts Daughters of the American Revolution, “Who lies Here: King Family Plot,” Taunton Daily Gazette, July 21, 2011, Web December 19, 2024, https://www.tauntongazette.com/story/news/2011/07/21/who-lies-here-king-family/38216968007/.

⁹ Hartley, Ironworks, 275.

¹⁰ Innes, Creating the Commonwealth, 265. Bar-iron (or wrought iron) could be turned into blister steel, the primary ingredient for crucible steel, considered the finest steel in the world and preferred by tool makers.

¹¹ For a more complete discussion of the Leonard family and genealogy, see Charles Bradford “Brad” Leonard’s James Leonard, Ironworker of Taunton, Massachusetts, Volume 1: The First Six Generations of His Descendants (Lulu Enterprises: Missoula, MT, 2011). Brad passed away in April 2023. After his death, his wife edited and expanded Brad’s original work, a collection now held by the Old Colony History Museum.

¹² Rev. Perez Forbes, “Topographical Description of Raynham” (Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1810), 3:175.] Forbes was a Leonard.

¹³ Innes, Creating the Commonwealth, 263.

¹⁴ Hartley, Ironworks, 276.

¹⁵ “In Board of Alderman,” July 5, 1899, Old Colony History Museum, Leonard files VL 552 M.

¹⁶ The Robert Treat Paine statue would be dedicated in 1904.

¹⁷ “An Embarrassment of Riches,” The Taunton Herald-News, vol 22, №175, January 4, 1902, Old Colony History Museum, Leonard files VL 552 M.

¹⁸ “Prospects of Leonard Family Monument,” Fall River Evening News, January 18, 1902, 5. The current fountain in the middle of Taunton Green is the Walter T. Soper Memorial Fountain, which replaced the Marvel Fountain in 1959

¹⁹ “Robert Treat Paine Memorial, Sculpture,” Art Inventories Catalog, Web, December 21, 2024, Robert Treat Paine Monument, (sculpture).

²⁰ “Taunton’s $100,000 Monument,” The Boston Globe, Sunday, September 14, 1902, 44.

²¹ Hanna, A History of Taunton, 278–279.

²² “Obituary,” Fall River Evening News, May 8, 1905, 8. Also, “Josiah R. Leonard Dead,” Fall River Evening News, May 21, 1908, 7.

²³ “Taunton,” Fall River Daily Evening News, April 26, 1899, 6.

²⁴ “Another Monument,” possibly The Taunton Daily Gazette, 1901, Old Colony History Museum, Leonard files VL 552 M.

²⁵ “Another Monument,” possibly The Taunton Daily Gazette, 1901, Old Colony History Museum, Leonard files VL 552 M.

²⁶ “Standing Lincoln,” Chicago Monuments Project, Web December 20, 2024, Standing Lincoln — Chicago Monuments Project.

²⁷ “Taunton’s $100,000 Monument,” The Boston Globe, Sunday, September 14, 1902, 44.

²⁸ “An Embarrassment of Riches,” The Taunton Herald-News, vol 22, №175, January 4, 1902, Old Colony History Museum, Leonard files VL 552 M.

²⁹ Letter from Lewis A. Leonard to Henry M. Lovering, December 31, 1901, Old Colony History Museum, Leonard files VL 552 M.

³⁰ “Leonard Monument: Memorial to Cost $100,000 to Be Erected at Taunton,” The Fall River Daily Herald, September 13, 1902.

³¹ “Carnegie Library,” Wikipedia, Web December 20, 2024, Carnegie library — Wikipedia. Also, “Taunton Public Library,” Wikipedia, December 21, 2024, Taunton Public Library — Wikipedia.

³² Letter from Lewis A. Leonard to James E. Seaver, July 19, 1902, Old Colony History Museum, Leonard files VL 552 M.

³³ “The Leonard Memorial,” The Lima Times-Democrat, Lima, Ohio, July 25, 1902, 6.

³⁴ Letter from Lewis A. Leonard to George H. Leonard, December 10, 1902, Old Colony History Museum, Leonard files VL 552 M.

³⁵ “The Iron Monument,” Taunton Daily Gazette, September 12, 1902, Old Colony History Museum, Leonard files VL 552 M.

³⁶ Letter from Lewis A. Leonard to James E. Seaver, December 30, 1902, Old Colony History Museum, Leonard files VL 552 M.

³⁷ Old Colony Historical Society, Leonard files VL 552 M.

³⁸ Letter from Charles Henry Niehaus to James E. Seaver, March 5, 1903, Old Colony History Museum, Leonard files VL 552 M.

³⁹ Letter from Lewis A. Leonard to James E. Seaver, April 16, 1903, Old Colony History Museum, Leonard files VL 552 M.

⁴⁰ Ibid.

⁴¹ “Job M. Leonard Had No Family Successor: Hence the Machinery in His Big Plant Was Dismantled — Career of Leonards in Iron Industry.”, The Evening Herald, Fall River, August 15, 1905.

⁴² “Nail (fastener),” Wikipedia, Web December 6, 2024, Nail (fastener) — Wikipedia.

⁴³ “Job M. Leonard Had No Family Successor: Hence the Machinery in His Big Plant Was Dismantled — Career of Leonards in Iron Industry.”, The Evening Herald, Fall River, August 15, 1905.

⁴⁴ “Site of the First Successful Iron Works in the Old Colony, 1656–1876,” December 21, 2024, Site of the First Successful Iron Works in the Old Colony Historical Marker.

⁴⁵ George Austin, August 9, 2015, “The Cost of Preserving History,” South Coast TODAY, Web, December 21, 2024, The cost of preserving history.

⁴⁶ “This House Was Once the ‘Most Elegant” in Somerset Village — and Now Could Be Yours,” The Fall River Herald News, November 10, 2021, Web, December 20, 2024, Historic Somerset home for sale; was built for ironworks owner Leonard.

⁴⁷ “Josiah R. Leonard Dead,” Fall River Daily Evening News, May 21, 1908, 7.

⁴⁸ Letter from Carolyn B. Owen, Archivist at the Old Colony Historical Society to Mrs. William T. Leonard, St. Michaels, MD, November 22, 1978, Old Colony History Museum, Leonard files VL 552 M.