The Golden Age of Radio in the Old Colony (Three Acts)

By Eric B. Schultz

Act One: An Old Colony First

December 1906. A 420-foot tubular steel antenna rises from Brandt Rock, a snowy, desolate spot along the Atlantic coast in Marshfield some 40 miles northeast of Taunton and 20 miles from where the Mayflower landed.

Under the direction of radio pioneer Reginald Fessenden, this monstrous tower is sending and receiving Morse code to a sister facility on the West Coast of Scotland. However, in early December its Scottish twin is toppled in a storm. Ever resourceful, Fessenden adds a General Electric transmitter in his Brandt Island transmission facility and decides to conduct a demonstration of “wireless telephony,” soon to be known as radio.

Three days before Christmas Eve, he sends notice to a handful of U.S. Navy and United Fruit Company vessels plowing the Atlantic which possess the necessary wireless signal detector. Then, on Christmas Eve 1906, the first “one-to-many” radio broadcast in history is hosted by Fessenden. After a brief welcome, he plays a recording of “Handel’s Largo,” performs his own violin solo, reads a passage from the Bible, and closes by wishing his floating Atlantic audience a Merry Christmas. “We got word of reception of the Christmas Eve program as far down as Norfolk, Va.,” Fessenden wrote.

Already home to many American firsts, the Old Colony could now claim the first radio broadcast.

Act Two: Wildfires in the Old Colony

Thanks to innovators like Reginald Fessenden, radio technology improved rapidly in the 15 years following his Christmas Eve broadcast. The watershed year for commercial AM radio in the United States would be 1922 when the industry exploded from a few dozen stations to more than six hundred. In the Old Colony, AM radio grew like wildfire, though some of the fires burned longer and more brightly than others.

In May 1922, for example, commercial radio launched in New Bedford when WDAU broadcast from the Slocum & Kilburn general hardware store on North Water Street. The station was constructed by the store’s radio department manager, Irving Vermilya. Already an accomplished amateur radio operator, Vermilya had been broadcasting his own programming from his residence in Mattapoisett.

When WDAU folded after less than two years, Vermilya installed the station’s equipment in his Mattapoisett home, obtained a commercial license, and returned to the air as WBBG, “The Voice of Cape Cod,” broadcasting every Wednesday evening. Less than two years later, unable to pay the ASCAP fees required to play music, Vermilya partnered with Armand J. Lopez and returned the station to New Bedford. With main studios located in the New Bedford Hotel, the newest reincarnation of Vermilya’s station became WNBH, from which he retired as chief engineer in 1955.

Known as “The Voice From Way Down East,” WMAF began its broadcast life on July 1, 1923, from the 300-acre estate of “Colonel” Ned Green in South Dartmouth. A colorful character himself, the Colonel had inherited $175 million from his mother Hetty Green, a New Bedford native known as the “Witch of Wall Street” and likely the richest woman in America when she died in 1916.

The Colonel was fascinated by technology and willing to invest in its development. He built state-of-the-art studios and, alongside his own local programming, transmitted entertainment from WEAF in New York City, an early example of network radio. He also created a drive-in facility, placing enormous outdoor loudspeakers around the top of his Round Hills estate water tower so that his neighbors without radios could pull up and listen.

Despite this well-funded and impressive start, WMAF ceased its regular broadcasts in the summer of 1928, and, three years later forfeited its license.

WSAR in Fall River also got its start in 1923 using a slogan “Fall River Looms Up” to capitalize on the city’s dominant textile industry. By the early 1940s, the station offered listeners the play-by-play of Boston’s two major league baseball teams. Like WNBH, WSAR would survive and thrive into the modern era.

Taunton’s first radio station went on air in October 1924. Owners Al and Dot Waite broadcast 10 watts of power from their furniture store on Weir Street, settling on the eponymous call letters, WAIT. AM radio technology was still primitive, however. “When a broadcast was planned,” William Hanna wrote in his History of Taunton, “station personnel went around to as many radio owners as possible to help them synchronize the tuning of their sets — not an easy task.”

Nonetheless, Tauntonians heard the results of the 1924 elections and play-by-play of the 1924 World Series. The Waites also broadcast live music from the Lincoln Piano Company on Main Street.

WAIT remained on the local dial at 1400 until 1927, Hanna adds, when the owners, needing to upgrade equipment to keep pace with regulations and technology, called it quits.

Intermission: The Fastest Growing Industry Known to Mankind

Old Colony residents who responded to the 1930 Census were asked a question that would have baffled most of them a decade earlier: Did they own a “radio set”? This question was the first ever in a U.S. census to ask about a consumer product and reflected the growing power of this new medium.

By 1930, there were more than a half million workers making radios, almost 44,000 retailers selling them, and some 626 U.S. radio stations broadcasting news and entertainment. The New York Times estimated radio’s contribution to the economy at more than a half billion dollars annually, calling it “the fastest growing industry known to mankind.” In nearly a decade, radio had been adopted by more American homes than the telephone or electric light had reached in nearly a half century.

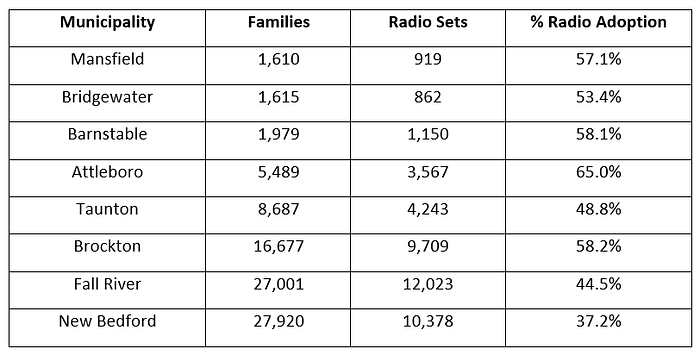

When tabulation of the 1930 census was complete, the government reported that slightly more than 40% of American families owned a radio set. In the towns and cities of the Old Colony, radio penetration was almost uniformly higher than the national average, a tribute to the “wildfires” of the preceding decade. Some 65% of Attleboro’s 5,500 families had radios, 58% of families in Barnstable and Brockton, and nearly that high a percentage in places such as Mansfield and Bridgewater. At 48.8%, Taunton’s 8,687 families were well above the national average for radio ownership.

A decade later, 82% of U.S. households owned a radio, including 92% in Massachusetts. The industry was well into what media historians would call its “Golden Age,” from the mid-1920s to the advent of television. Families around the country would gather to listen to their favorite programs, including Amos & Andy, Rudy Vallee, the Atwater Kent Hour, Lucky Strike, and the Camel Pleasure Hour.

Act Three: The Golden Age of Radio in Taunton

For many Taunton residents, however, the golden age of radio really began when J. Milton Hammond wandered into town in the late 1940s looking to launch a radio station. A native of the Pittsburgh area, Hammond had been a record promotor for RCA who loved big band music but had grown tired of chasing his clients around the countryside. By the mid-1940s he had caught the radio bug.

Visiting Bob Phillips in his music store on Broadway, Hammond asked for the names of quality local lawyers who might help him establish an AM station. Phillips suggested J. Marshall and Marguerite McGregor, who would soon become Phillips’ partners.

In 1948, Silver City Broadcasting Corporation was granted a construction permit to erect a transmitting tower at 760 County Street. On December 22, 1949, WPEP-AM signed on as a 1,000-watt “sunrise to sunset” station at 1570 kilocycles. Its studios were on the second floor of the Roseland Ballroom. The McGregors had promised local merchants they would be on the air by Christmas 1949 and they delivered. “We were so busy,” their daughter Laurel remembered, “that nobody had time to buy Christmas presents.”

Co-owner and now station manager J. Marshall McGregor organized the first day’s programming, which included news every half-hour, sports and weather, sidewalk interviews with pedestrians on Broadway, and a live broadcast from a children’s Christmas party being held on the stage of the Grand theater. WPEP was launched as a “full service” radio station and the McGregors ensured that it maintained a strong local presence and flavor through their three decades of ownership.

The first staff members included experienced broadcasters from Providence, Pawtucket, and Fall River. In time, co-owner Marguerite McGregor would serve as hostess of two WPEP staples, “News and Views” and “Women’s World.” When she died in 1991, Mayor Richard Johnson described her as “a true founder of radio communication in Taunton. Anyone who listens to WPEP associates Marguerite McGregor and her family with radio communication in the city.”

Another personality to emerge behind a WPEP microphone was Joseph G. Quill, whose long career would take him from Armed Forces Radio in Japan, to station manager of WPEP, to co-owner of Taunton’s first FM station, WRLM. For some Tauntonians such as retired broadcaster Anthony Lopes, however, “Joe Quill” meant a mad dash home at lunchtime from Hopewell School during the 1954 school year. “At 11:45 a.m. Monday through Friday,” Lopes recalled in his memoir, “it was ‘The Uncle Joe Show.’ Uncle Joe was a fictional character played by Joe Quill, the station manager. It was a kids’ show with stories and records featuring The Lone Ranger, Brer Rabbit, Bugs Bunny, and of course, ‘Mighty Mouse’ to save the day. It was great entertainment,” Lopes wrote, “and I could hardly wait each day for the 30 minute show.”

Quill was followed by another iconic WPEP personality, Eddie Litchfield, considered by many to be the “Voice of Taunton.” Born in the city, he was a 1931 graduate and football star at Taunton High School and later an announcer at the Taunton and Raynham dog tracks. In 1951, while employed as a clerk at Grossman’s, Litchfield was offered a part-time job announcing football games on WPEP. This began a 40-year career on the station as a disc jockey, talk show host, newsman, and announcer for the annual Taunton High/Coyle-Cassidy Thanksgiving Day football game.

“They said they would take me on as a temp,” Litchfield flashed his famed humor in 1989, “and no one has said anything to me since so I’m still here.”

In a world where media changed rapidly and companies came and went, WPEP had a long and successful run in Taunton, though not without its own twists. In 1962, the station moved its studios from Roseland to a white frame house on Broadway; twenty years later, it moved to Liberty Lane near the Taunton Green, with subsequent ownership locating it some six miles out of town on Route 44.

As the Big Bands faded and 78s turned to 45s, Litchfield hosted the station’s first talk show, “PepTalk.” Laurel McGregor, just a teenager when the station launched in 1948, became news director and host of her own popular afternoon talk show, “On the Green.”

Litchfield and McGregor were joined by Affonso Ferreira-Mendes’s “The Portuguese Hour”; Senator John F. Parker’s “Under the Golden Dome”; Harold O. Woodward and Malcolm Hill reporting on the “Bristol County Farm Journal”; Sylvia White’s “Church Woman’s Scrapbook”; Harry Gale’s “Taunton Notes”; and Deborah Setchell’s “Homemaking.”

After its sale in 1977 by the McGregors, the station changed hands several times, operating in a world of increasingly competitive FM radio and new challenges such as the Internet, iTunes, and satellite broadcasting. The curtain finally fell on WPEP in October 2007, almost 60 years after its launch.

Today, radio in the Old Colony remains healthy and vibrant, a tribute to the savvy of modern owners. However, today’s local broadcasters stand on the shoulders of legendary Old Colony entrepreneurs such as Brandt Rock’s Reginald Fessenden, New Bedford’s Irving Vermilya, and Taunton’s McGregor family.

N.B.

Donna L. Halper and Christopher H. Sterling do a careful analysis of fact vs. fiction in “Fessenden’s Christmas Eve Broadcast: Reconsidering an Historic Event,” The Antique Wireless Association Review, Volume 19, 2006, 119–137. See also Carrie Crane, “The Golden Era of Radio,” https://www.boylstonhistory.org/category/The_Golden_Era_of_Radio/c124. True or not, the story of Fessenden’s first broadcast has become an accepted part of broadcast history.