Reverend Samuel Hopkins Emery and the “World’s Greatest Showman”

By William F. Hanna

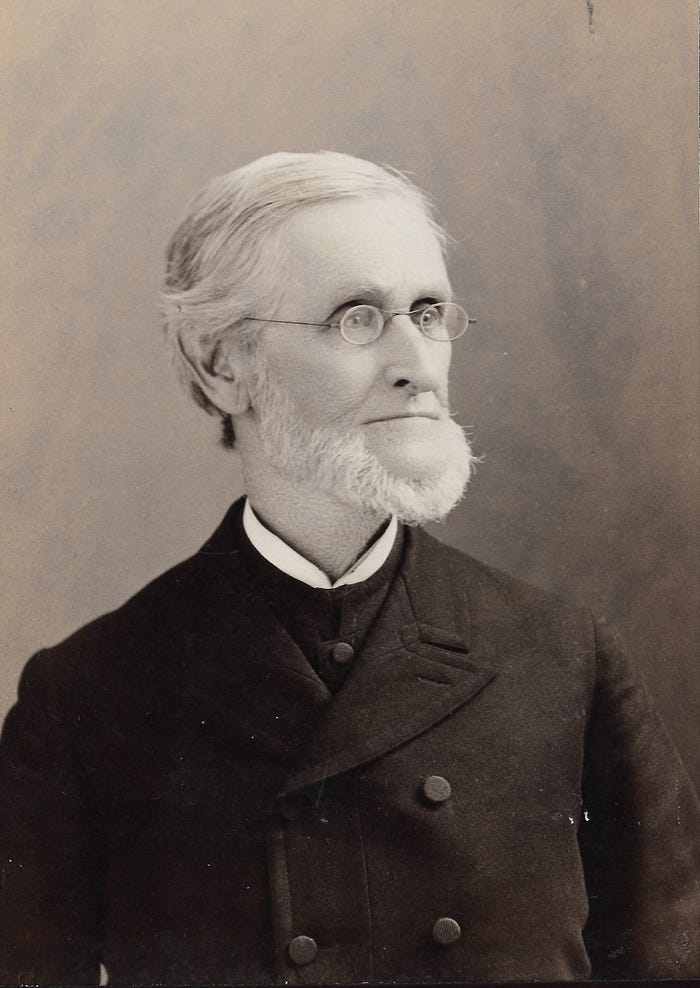

In the spring of 1852, as Reverend Samuel Hopkins Emery was writing his two-volume church history of Taunton, he came upon a research problem that brought his project to a halt. A talented biographer, Emery was producing a chronological study of the local ministry when he came up short on information about one of its most illustrious members. After trying unsuccessfully to find someone locally who could answer his questions, Emery decided to look for help outside of Taunton.

The cleric in question was Reverend Caleb Barnum, and just about everyone in town knew at least something about him. Born in Connecticut in 1737, Barnum was one of Taunton’s Revolutionary War heroes. Installed in February 1769 as the seventh minister of the town’s first Congregational church, he was an outspoken advocate for the whig cause in the years leading up to American independence. Among his congregation were several of the town’s most prominent patriot families, including those of Robert Treat Paine and David Cobb. In October 1774, as demonstrators prepared to raise the Liberty & Union flag on Taunton Green, Barnum gave a fiery address in support of the action, and Emery writes that six months later, when word of the battle at Lexington reached Taunton, the minister again took to both stump and pulpit to urge his townsmen to do their part in resisting British tyranny.

Emery knew all of this and more about Barnum’s Revolutionary passion. Most famously, in February 1776, the minister asked his Taunton congregation for a one-year leave of absence so he could enter the army as a chaplain. The request was granted and he enlisted in the 24th Regiment, Continental Infantry, under Colonel John Greaton. The Taunton minister took part in the siege of Boston until the British army evacuated the city and then he left for duty in New York. A month later Barnum’s 24th Regiment was ordered to Canada, where it suffered severely during the American defeat at Trois-Rivières.

After the battle, as the Americans withdrew southward, Barnum made it as far as Fort Ticonderoga before falling seriously ill. Discharged because of sickness on July 24, he left the army and started for Taunton. Overtaken by his illness in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, he languished at the home of a friendly minister for three weeks before dying on August 23, 1776. In a letter informing the citizens of Taunton of his death, the Pittsfield clergyman remembered that on his deathbed, when asked about the righteousness of the American cause, Barnum said, “I have no doubts concerning the justice and goodness of that cause, and had I a thousand lives, they should all be willingly laid down in it.” He was buried in Pittsfield, but his wife and seven children remained in Taunton.

Emery, writing his history, was familiar with that as well, but he needed a different kind of information. As part of each biographical sketch, he liked to include as much genealogical material as possible, but there was almost nothing available on Caleb Barnum. Some Barnum descendants still lived in Taunton, but when they weren’t able to answer his questions, he resolved to cast a wider net. In fact, he decided to write to Bridgeport, Connecticut, to the home of the world’s best-known Barnum.

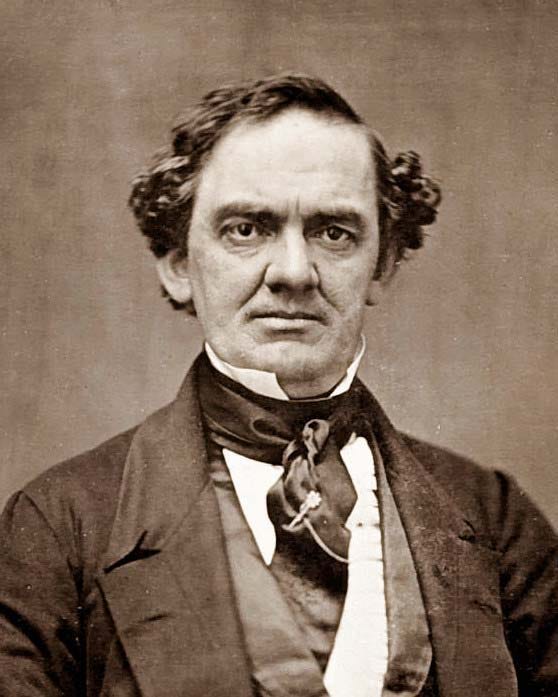

At 42-years old, Phineas Taylor Barnum was among the most famous showmen on either side of the Atlantic Ocean. A former newspaper owner and editor, he had been at the forefront of show business for more than a decade. His American Museum, displaying all sorts of “natural curiosities,” had opened in New York City in 1841 and each year it continued to attract thousands of visitors, everyone willing to pay twenty-five cents for admission. Looking to appeal to a wider market, Barnum had garnered international headlines in 1844 when he accompanied his diminutive star, Charles Stratton, aka General Tom Thumb, to Buckingham Palace for an audience with Queen Victoria. And later, as if to prove that his tastes weren’t entirely lowbrow, Barnum had brought Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale, to the American stage in a tour that was just ending in May 1852.

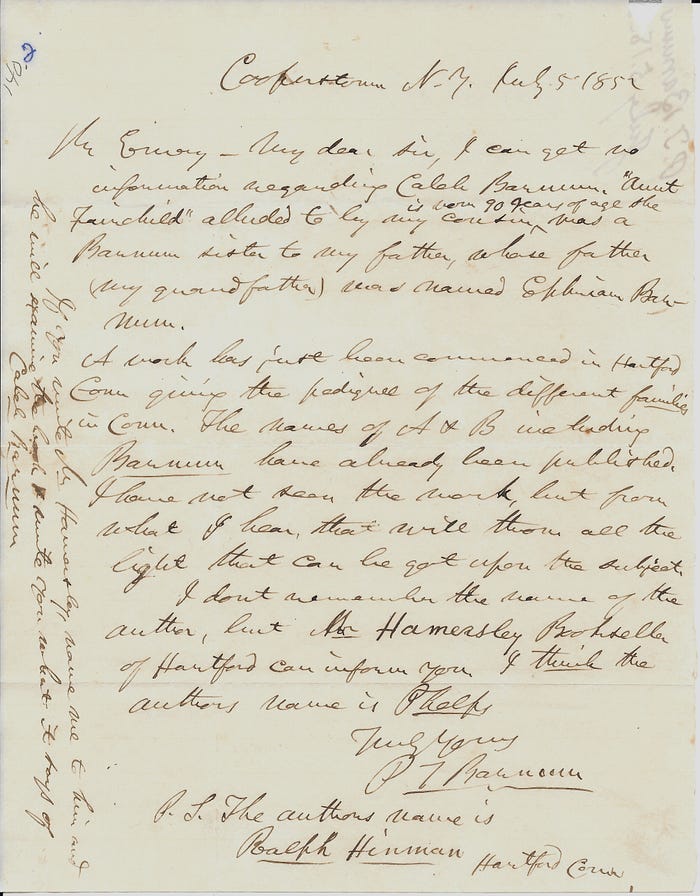

Reverend Emery wrote to Barnum asking if he had any family history to share on the Revolutionary War hero with the same surname. Unfortunately, we don’t have Emery’s original inquiry, but the showman took the request seriously and responded with the most helpful reply possible. Barnum’s correspondence is in the collection of the OCHM. Writing from Cooperstown, New York on July 5, 1852, the entertainer reported that he had been unable to find any information on Caleb Barnum, despite having checked with a 90-year old aunt. He also said, however, that Ralph Hinman, a Hartford man, was writing a book on the prominent families of Connecticut, and he suggested that Emery contact this writer for information. Barnum knew Hinman, and he gave Emery permission to use his name as a means of introduction. “Name me to him,” wrote the showman, “and he will examine the book and write you what it says of Caleb Barnum.” Emery did that and apparently the material Hinman sent was helpful.

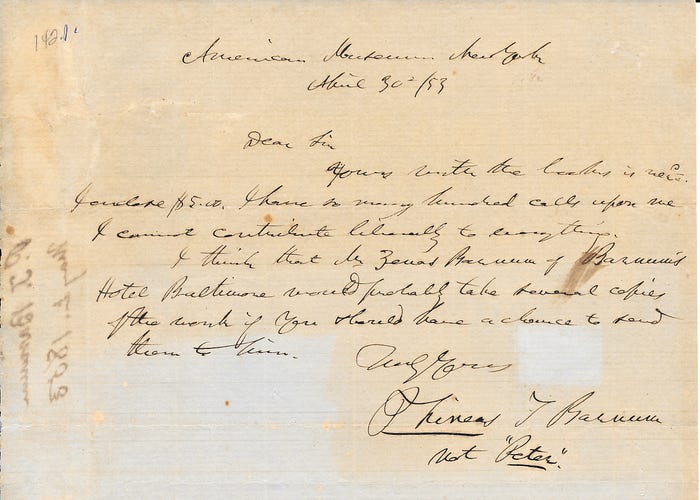

Emery wrote at least two additional letters to Barnum, the first asking him to join the list of subscribers whose support would help meet the costs of publishing the church history. Barnum must have agreed because on April 30, 1853 he replied from New York City acknowledging receipt of The Ministry of Taunton, Emery’s two-volume work that had just been released. Barnum told Emery that he was enclosing $5 for only one copy. “I have so many hundred calls upon me,” explained Barnum, “that I cannot contribute liberally to everything.” Again, however, the showman extended himself in an effort to help Emery’s project. “I think,” he said, “that Zenas Barnum of Barnum’s Hotel Baltimore would probably take several copies of the work if you would have a chance to send them to him.”

In the same letter we learn that Barnum actually looked inside the book. He was no doubt pleased to see his name listed among the nearly 500 subscribers, where “PT Barnum, Esq., Bridgeport, Conn.” took its place alongside Daniel Webster, Charles Sumner, Rufus Choate and other political and cultural luminaries. But everybody makes mistakes and show biz people can sometimes be more sensitive. Less satisfying to the entertainer was Reverend Emery’s gaffe of citing him in the text as “Peter T. Barnum, Esq., of Bridgeport.” That misstep annoyed Barnum just enough to cause him to close his April 30 letter with this correction. He was, after all,

Phineas T. Barnum

not “Peter”