Fire and Ice: Some Calamities of the Old Colony : Part II

Eric B. Schultz

In part I of this post, we described some of the Old Colony’s most devastating fires, including the Granite Mill Blaze in Fall River (1874), the Grover Shoe Factory Disaster (1905) and the Strand Theatre Fire (1941) in Brockton, and the Myles Standish Forest Fire (1964). We also recapped the fiery eruption of the volcano on Tambora in Indonesia (1815) that inverted weather patterns worldwide and froze the Old Colony in 1816. This so-called “year without a summer” is a perfect introduction to part II of our series on Old Colony calamities, which features another dose of record cold and snow.

Our story begins on Monday morning, February 6, 1978. It’s a chilly winter day, the start of a school and work week. Some of our Baby Boomer and Gen X readers will remember vividly where they were that morning.

Just two weeks before, the Old Colony had been buried in twenty inches of snow, a storm that meteorologists had struggled to forecast accurately. The wind and tides had failed to live up to their billing. Some weathermen — and they were almost exclusively men in 1978 — had predicted mostly rain. So, meteorologist Eric Fisher writes, the perception about this next February snowstorm “was that it was overblown and would not live up to the hype.”[1]

The forecast called for snow to develop on Sunday night, followed by blizzard conditions. However, at 6 a.m. on Monday, there wasn’t a snowflake in the sky. Confident that weather forecasters were confused again, commuters headed to work. School superintendents breathed a sigh of relief and released morning buses to their routes.

The first flakes appeared around 8 a.m. By noontime, snow was falling in southern New England at the rate of two inches per hour. Now panicked, officials closed schools early, and bosses dismissed employees. For many commuters, however, it was too late.

Nearly 2,000 vehicles became trapped on Routes 95, 195, and 146, and 3,500 on an eight-mile stretch of Route 128.[2] Travelers who abandoned their vehicles in the middle of an interstate wouldn’t be reunited with their cars for days. Employees of Boston Garden and hundreds of fans who insisted on attending the Beanpot Tournament that evening would find themselves sleeping for several nights in Garden skyboxes.

A foot of snow fell by midnight. Winds reached 90 MPH. A “supermoon” brought record tides to the Old Colony’s Cape and South Shore.

Officials in Rehoboth tried to clear the town’s 166 miles of roads, struggling to move 11-foot drifts. Good Samaritans on skimobiles rescued stranded motorists. The town’s ambulance was stuck in Providence on its return from Rhode Island Hospital. “A Homestead Ave. resident,” the Taunton Daily Gazette reported, “went into labor during the storm and was transported to Sturdy Memorial Hospital in Attleboro by Metro Ambulance, behind a snow plow.”[3]

In Dighton, tow trucks had to be freed from drifts on Williams Street near the Taunton Dog Track. Highway Superintendent Alfred Perry said some secondary streets were “lost,” but his crews were able to open at least one lane for about 75 percent of the main roads.[4]

Taunton Street Superintendent Joseph E. Terra asked residents of the city to be patient as power outages struck many neighborhoods. “It took us three hours to get down Scadding St.,” he said. “And we just got word that it’s snowed in again so we’ll have to get back out there with plows.”[5]

Meanwhile, volunteers for Taunton Civil Defense worked to get nurses to Morton Hospital and ensure adequate staffing at that critical facility.

To add insult to injury for Taunton-area diners, an explosion and two-alarm fire on February 5 destroyed the popular Gondola Restaurant on Bay Street. (Fortunately, it would rise from the ashes.)

In Raynham, plows battled eight-foot drifts to keep North and South Main Streets and other main thoroughfares passable. A roof collapse at the Raynham Aquarium and Pet Store at the King’s Plaza on Route 44 required the rescue of parrots and other small animals. One police officer took three puppies home to care for them.[6]

The Howard Johnson’s Restaurant on Route 24 in Middleboro provided overnight lodgings to eight people whose vehicles were stuck on Routes 24 and 25. More than a third of Lakeville lost power. In Norton, police and civil defense opened the Middle School to about 50 residents in need of shelter.[7]

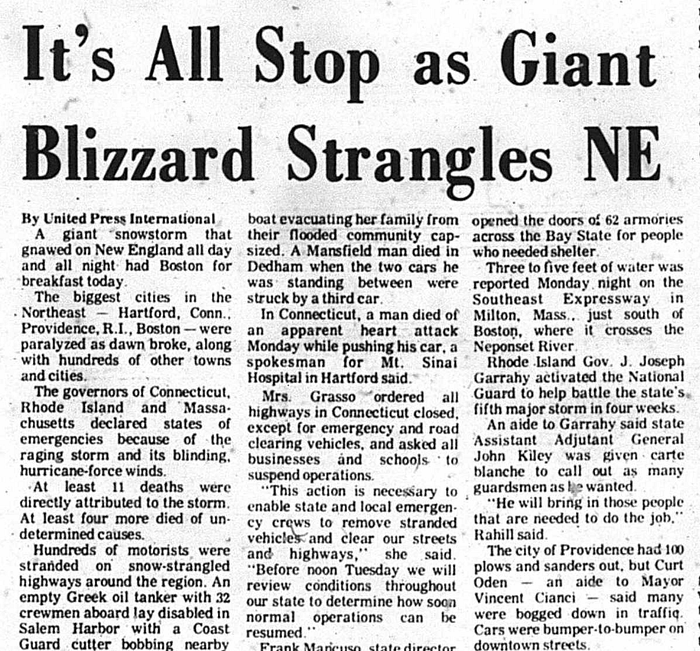

Perhaps United Press International said it best with its headline, “It’s All Stop as Giant Blizzard Strangles NE.”[8]

As the storm raged, more than 11,000 people fled their homes in low-lying coastal areas. Towns battled downed wires and sought empty parking lots to deposit snow. By February 8, Lakeville had exhausted its annual snow-removal budget.[9]

Not everything was grim. With driving bans in Taunton and other communities enforced through February 9, residents around eastern Massachusetts donned snowshoes and cross-country skis. Neighbors who had met only in passing found themselves at impromptu all-night parties. The roads were peaceful, Old Colony vistas taking on the look of a Currier and Ives print.

Known officially today as the “Northern United States Blizzard of 1978,” this massive February storm dropped more than 29 inches on Providence, 27 on Boston, and 20 on Worcester. The snow, winds, and cold killed some 100 people in Massachusetts and Rhode Island and caused more than $2 billion in damage.[10] While most nor’easters last six to 12 hours, this one sat atop the Old Colony for 33 hours.[11]

The Blizzard of ’78 was the first storm to receive extensive television coverage, confirming that calamity could generate ratings. Today, as weather reporting veers into performance art with frozen reporters standing outdoors in raging storms to prove to viewers that yes, it’s snowing, blame it on 1978. And, when 60- and 70-somethings race to the store for milk and batteries at the first sign of snow flurries — that, too, is the long, snowy shadow of the Blizzard of ’78.

Other Old Colony Snowstorms

Some of the Old Colony’s most remarkable storms occurred before the advent of modern weather forecasting, their details captured by word of mouth and personal journals. “The winter of 1747–48 was one of the memorable winters that used to be talked about by our grandfathers when the snow whirled above deep drifts around their half-buried houses,” historian Sidney Perley wrote in 1891. Some 30 storms that winter left five feet of snow throughout New England, and the only form of travel was by snowshoe.[12]

Likewise, the Old Colony received five feet of snow in December 1716, followed by several storms in January 1717 that, Perley writes, “lay in drifts in some places twenty-five feet deep.” Minister Cotton Mather found neighbors overwhelmed with snow even before another great storm rolled in on February 18, canceling religious meetings. The storm destroyed orchards and buried livestock. One farmer lost 1,100 sheep. “Many a one-story house was entirely covered by snow,” Perley added, while Native Americans “who were almost a hundred years old, said that they had never heard their fathers tell of any storm that equaled this.”[13]

The Blizzard of 1888

Just at the cusp of modern forecasting, one storm rivaled the Blizzard of ’78.

Between March 11 and 14, 1888, The Great Blizzard of 1888 — also called The Great White Hurricane — deposited between 10 and nearly 60 inches of snow from New Jersey to northern New England. Ground zero was the Hudson Valley, but New York City was brought to a standstill, western Massachusetts was buried, and some residents of the Old Colony were stuck in their homes, unable to clear a path from their doorways.

Towns around the region were isolated as train service halted and telegraph lines fell. On March 13, the Taunton Daily Gazette notified its readers that communications with the outside world had been severed. The paper warned that “if there is a paucity of news in our telegraphic columns to-day the cause will be readily understood and all the papers in New England will keep us company.”[14]

In New Bedford, the boat for New York on the evening of March 12 returned a half hour after it had departed, unable to make headway. The Vineyard steamers remained tied to their docks. “A heavy derrick sixty-five feet in height in the coal yard of John Duff on Fish Island fell with a crash.”[15]

The Boston Globe boasted about its recently installed, new-fangled device called a telephone, saying, “The copper wires of the New England Long Distance Telephone Company refused to be downed.” The paper’s March 14 editions featured headlines: “Maine roads covered by drifts”; “Boston passengers sleep in a train”; “Farmers in Vermont imprisoned”; “Fishing craft ashore at Portland.”[16]

About 400 people in the Northeast died, and 100 died at sea as some 200 ships sank off the East Coast.[17]

Like the Blizzard of ’78, the Blizzard of 1888 became a standard against which all future storms would be measured. “Fall River awoke this morning,” a local paper reported on September 12, 1889, “still in the grasp of a storm which seems likely to become historical . . . [though] not as severe as the memorable blizzard of March 1888.”[18] The following winter, the paper reported on “the most severe snow storm since the blizzard of 1888.”[19] Four years later, the paper reported on “the heaviest fall of snow in years,” making it the “worst blizzard since 1888.”[20]

More than half a century later, a storm that blanketed New England in March 1940 was “reportedly the worst since the famous blizzard of 1888.”[21]

“I don’t need to search the records on the Blizzard of 1888,” Boston Globe reporter Roy Johnson wrote in 1967. “I was there in person, a 5-year-old. I can recall flattening my nose against a window pane and wondering whether my father was going to make it. He did. But other dads were found dead in deep drifts by rescue parties.”[22]

A wag at the New York Evening Sun reminded readers that, no matter how awful the storm, the sun would shine again. “March raised an extraordinary and offensive amount of meteorological Cain, but he became ashamed of himself, and his last days were his best days,” the reporter wrote in early April 1888 as the Northeast recovered from the Blizzard of 1888. “He is as sweet this morning as pie to New England mouths, as moonlight to the melodious cat, as spring to milliners, as Easter bonnets to the head and soul of woman. But the evil of March will long live after him.”

The reporter also noted, no matter how awful the storm, time and human nature would make it worse. “Ninety years hence,” he concluded, “the Oldest Inhabitant will be telling his great-grandchildren of the great blizzard of March 1888. And in all human probability, he will lie like thunder.”[23]

The third and final post in this series of Old Colony calamities — no lie — will feature all of the wind but none of the snow.

Continue reading:

Notes

[1] Eric P. Fisher, Mighty Storms of New England: The Hurricanes, Tornadoes, Blizzards, and Floods That Shaped the Region (Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot, 2021), 5.

[2] Fisher, Mighty Storms, 8.

[3] Jeanne Gilbert, “Rehoboth Struggles With 11-Foot Drifts,” Taunton Daily Gazette, February 7, 1978. Mother delivered the baby safely.

[4] “Dighton Digs Out,” Taunton Daily Gazette, February 7, 1978.

[5] “Storm Paralyzed Entire Area,” Taunton Daily Gazette, February 7, 1978.

[6] “Fire Razes Berkley Home; Raynham Pet Store’s Roof Collapses Killing Animals,” Taunton Daily Gazette, February 7, 1978.

[7] “Storm Paralyzed Our Entire Area,” Taunton Daily Gazette, February 7, 1978.

[8] Taunton Daily Gazette, February 7, 1978.

[9] “Town Loses Snow Budget,” Taunton Daily Gazette, February 8, 1978.

[10] Updated for today’s equivalent value. Melissa Hanson, “Massachusetts’ Worst Disasters: These Fires, Hurricanes and Explosions Have Devastated the State,” MassLive, November 4, 2018, Web August 30, 2022, https://www.masslive.com/news/erry-2018/11/fa8ce0cc02831/massachusetts-worst-disasters.html.

[11] Sophia, “The 11 Most Horrifying Disasters That Ever Happened in Massachusetts,” Only In Your State, January 11, 2016, Web August 30, 2022, https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/massachusetts/horrible-disasters-ma/.

[12] Sidney Perley, Historic Storms of New England (1891; reis., Lark’s Haven Publishing, 2009, loc. 1004.

[13] Perley, Historic Storms, loc. 708.

[14] “Broken Wires and Prostate Poles,” The Taunton Daily Gazette, March 13, 1888.

[15] “The Storm in New Bedford,” The Taunton Daily Gazette, March 13, 1888.

[16] Andrew L. Andrews, “Tales of the ’88 Blizzard Drift On,” The Boston Globe, March 12, 1988.

[17] Sophia, “The 11 Most Horrifying Disasters That Ever Happened in Massachusetts,” Only In Your State, January 11, 2016, Web August 30, 2022, https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/massachusetts/horrible-disasters-ma/.

[18] The Fall River Daily Herald, September 12, 1889.

[19] The Fall River Daily Herald, December 26, 1890.

[20] The Fall River Daily Evening News, February 13, 1894.

[21] “Snow Drifted Highways Cut Off Farm Communities,” The North Adams Transcript, March 25, 1940.

[22] Andrew L. Andrews, “Tales of the ’88 Blizzard Drift On,” The Boston Globe, March 12, 1988.

[23][23] From New York Evening Sun, “Ta, Ta, March!” Fall River Daily Evening News, April 2, 1888.